Optical illusions have played a role in human creativity for tens of thousands of years. The history of optical illusions is deeply intertwined with the history of art itself. We discuss the most famous illusions from prehistoric cave engravings to modern Op Art. By studying how artists have tricked the eye through the ages, we can learn about their understanding of human perception.

Prehistoric illusions

Some of the earliest known examples of optical illusions come from prehistoric art. One of the most remarkable is a carved spear-thrower from Canecaude, France, dated to about 14,000 years ago. The carving uses a single crescent shape that can be interpreted as either a mammoth’s tusk or a bison’s horn. It depends on which engraved eye the viewer focuses on. This makes it then one of the oldest examples of a reversible figure: an image designed to shift between two interpretations.

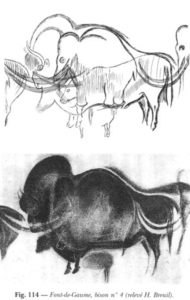

In the Font-de-Gaume cave, similar engravings play with overlapping mammoth-bisons in order to create ambiguous imagery. These illusions suggest that even prehistoric humans were experimenting with perception long before formal psychological science existed.

There is strong evidence to suggest that the prehistoric optical illusions were created intentionally:

- The use of natural contours of the rock walls enhanced the illusion of depth or movement, showing awareness how light, shadows and surface curvature affect perception.

- Overlapping figures seem to morph, hinting at an understanding of visual ambiguity.

- Techniques are repeated across different sites and time periods, suggesting they were part of a shared visual language.

- Experimental archaeology has also shown that these illusions come alive under flickering torchlight in ways that are far too deliberate to be a coincidence.

All of this points to a surprisingly sophisticated grasp of perception, long before the science of optics ever existed.

Ancient India: cultural symbolism in the history of optical illusions

Moving forward in time, we see illusions appearing in ancient architecture and sculpture in India. Some temple reliefs (like those at the Airavatesvara Temple) include animal illusions where a single figure resembles an elephant from one angle and a bull from another.

This shows an advanced understanding of visual ambiguity and the viewer’s perspective. And it reflects a long-standing cultural appreciation in India for the mystical and the illusory. These ideas are deeply embedded in Hindu philosophy, where maya (illusion) is a core concept.

Ancient Greece

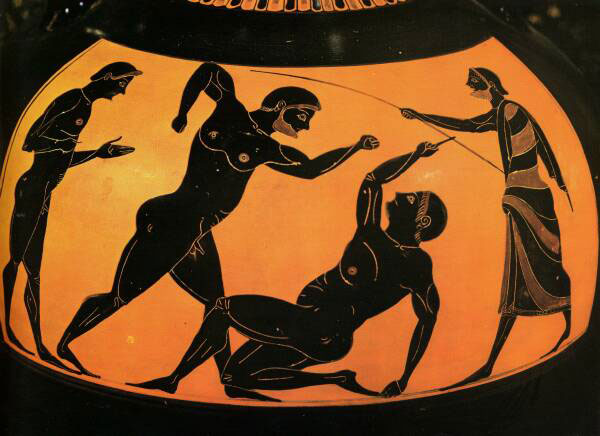

Ancient Greek artists were very aware of visual tricks, particularly in sculpture and pottery. On vases and amphorae, painters used clever line work, contrast, and geometric patterns to mimic depth, create movement, and play with symmetry.

In red-figure pottery, artists would often shade clothing folds or use overlapping limbs and foreshortening (depicting objects as receding into space) to give figures a sense of three-dimensional volume.

The Greek philosopher Plato famously discussed the limits of perception and how shadows and reflections can mislead the senses. These ideas would later influence Western philosophy and epistemology.

The Renaissance: Linear perspective and visual trickery

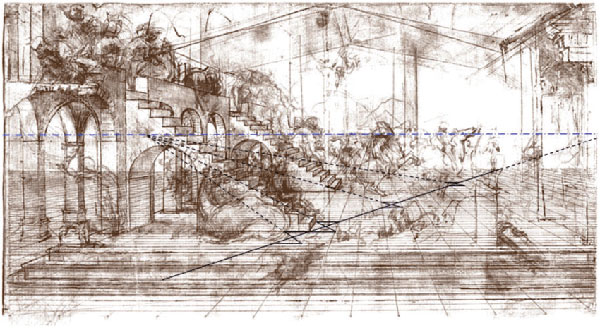

The invention of linear perspective during the Renaissance completely changed the way artists portrayed the world. Leonardo da Vinci, Piero della Francesca, and Andrea Mantegna began experimenting with vanishing points, horizon lines, and visual depth to make flat surfaces appear three-dimensional.

Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks include studies of light, shadow, and reflection. This shows a remarkably modern understanding of how the human eye processes visual information (centuries before the science of vision proved him right).

Some Renaissance artists went further, deliberately playing with perception.

One of the most famous examples is “The Ambassadors” (1533) by Hans Holbein the Younger. At first glance, it appears to be a detailed double portrait filled with symbolic objects, but across the floor is a strange object. When you view it from the correct angle, however, that smear becomes a perfectly rendered skull. This memento mori (a reminder of that you will die) was a common theme during the Renaissance.

The skull was created using a technique called anamorphosis, which distorts an image so that it only appears correct when viewed from a specific perspective.

The Gardener by Guiseppe Arcimboldo (ca 1587-90)

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, for example, painted portraits made entirely of objects like fruits, vegetables, and books forming a human face that dissolves into its parts the longer you look. These were early examples of ambiguous images, a key category of optical illusions still explored today.

Baroque optical illusions

Baroque artists took visual deception to theatrical new heights. During the 17th and early 18th centuries, painters and architects embraced the dramatic flair of trompe-l’œil, a technique designed to “trick the eye” into seeing three-dimensional space on flat surfaces.

You can find some of the most famous Baroque illusions in Italian churches and palaces. Andrea Pozzo’s ceiling fresco in the Church of Sant’Ignazio in Rome is a masterpiece of illusionistic architecture. From the correct viewpoint, the flat ceiling appears to open into a glorious dome, filled with ascending saints and golden light.

Trompe-l’œil Still Life by Rembrandt’s student Samuel van Hoogstraten played tricks with perspective and shadow, making paper curls, broken glass, and peeled paint look uncannily real.

20th century: Surrealism and impossible objects

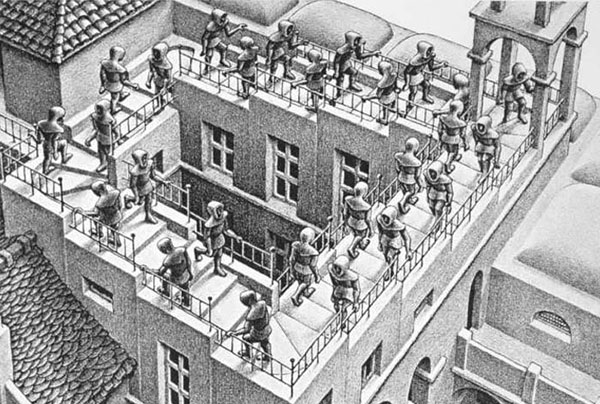

In the 19th century, interest in the psychology of perception led to deeper scientific exploration of optical illusions. Artists like M.C. Escher pushed this fascination into the 20th century, creating impossible objects, infinite staircases, and repeating patterns that seem to defy the laws of geometry.

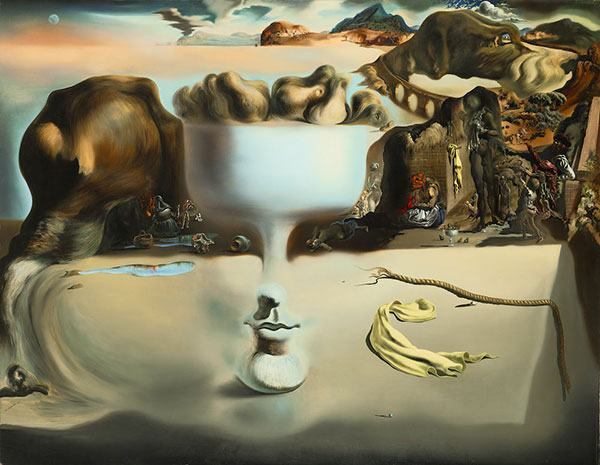

With the rise of Surrealism in the early 20th century, optical illusions took on a new role — not just to trick the eye, but to question reality itself. Artists like Salvador Dalí blurred the boundary between what is seen and what is imagined. Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach famously merges a dog, a landscape, and a human face into a single shifting image, depending on how you look at it.

These artists weren’t just playing with visual tricks — they used illusion as a philosophical tool to explore perception, identity, and the subconscious mind.

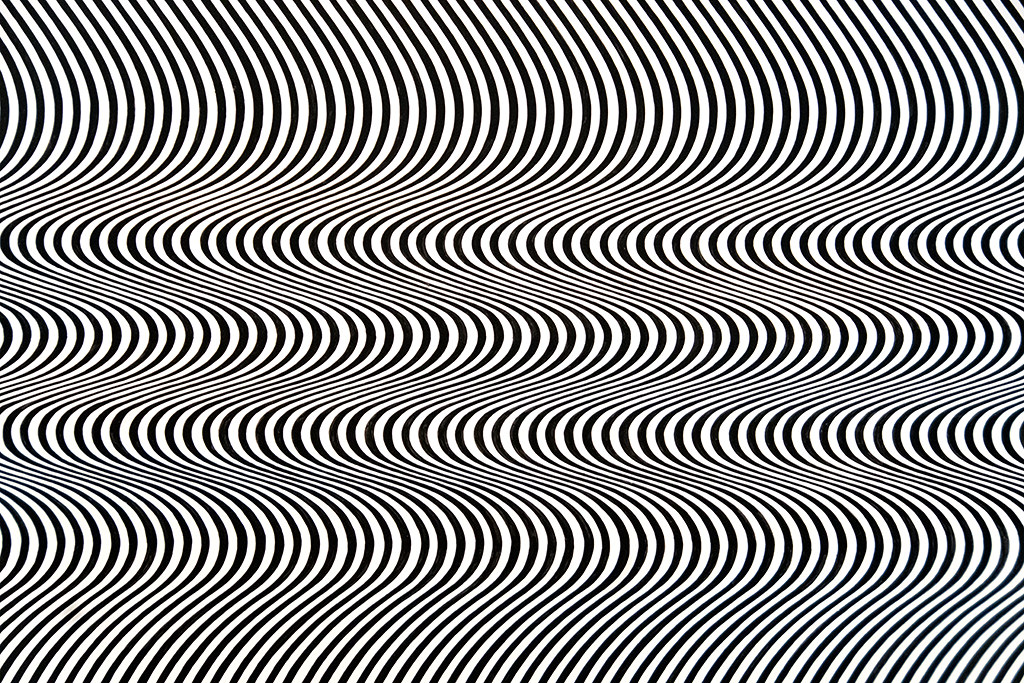

Op Art (short for “Optical Art”) emerged in the 1960s as a movement dedicated entirely to visual illusions. Artists like Bridget Riley created striking black-and-white patterns that seem to shimmer, vibrate, or move.

These illusions were not accidental. They were the result of careful experimentation with geometry, contrast, spatial relationships, and the way our eyes and brains process visual input.

The history of optical illusions isn’t just about tricking the eye — it’s also about revealing how we see. From prehistoric carvings to mathematical masterpieces, artists have always explored the tension between appearance and reality. All these illusions show that perception is not passive. It is an active process shaped by culture, experience, and design.